Code

data <- read.csv("/Volumes/anyan-1/frederickanyan.github.io/quantpost_data/happinesGSS12_long.csv")# Read the data for the analysis Frederick Anyan

June 15, 2023

August 30, 2024

We can analyse the association between two categorical variables in different ways (e.g., using stacked bar graphs or pie charts). The most common way is to use contingency tables with rows and columns displaying categories of each variable. The count or frequency of each pair of categories are given in a cell.

We will see how to analyse the association between two categorical variables using different functions in different packages in RStudio. The CrossTbale() function seems to be very popular as is the chisq.test() function. Another function is the ggbarstats() in the ggstatsplot package. This package produces beautiful plots and charts that are publication-ready with good quality. By plotting your pie chart or stacked bar graph, the ggpiestats() and the ggbarstats() function also compute the Chi-squared test statistic, with very useful information in addition, including a Bayesian effect size.

In this example, we will answer the research question: is family income associated with happiness? Following are questions asked in the General Social Survey (GSS).

“Compared to American families in general, would you say that your family income is below average, average, or above average?”

“Taken all together, would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?”

We start with the null hypothesis that:

To test the null hypothesis, we can use the CrossTable() function in the gmodels package. Note that the CrossTable() can take both raw data and contingency table.

CrossTable() functionLet’s see how the CrossTable() function works

data <- read.csv("/Volumes/anyan-1/frederickanyan.github.io/quantpost_data/happinesGSS12_long.csv")# Read the data for the analysis Let’s see how a cross tabulation of the data looks

library(gmodels) #Load the packgae to access the CrossTable() function

CrossTable(data$Income, data$Happy) #Get a cross tabulation of variables with cell counts/contingency table

Cell Contents

|-------------------------|

| N |

| Chi-square contribution |

| N / Row Total |

| N / Col Total |

| N / Table Total |

|-------------------------|

Total Observations in Table: 1733

| data$Happy

data$Income | not | pretty | very | Row Total |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

above | 29 | 178 | 135 | 342 |

| 4.356 | 1.413 | 8.709 | |

| 0.085 | 0.520 | 0.395 | 0.197 |

| 0.134 | 0.181 | 0.254 | |

| 0.017 | 0.103 | 0.078 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

average | 83 | 494 | 277 | 854 |

| 5.163 | 0.135 | 0.898 | |

| 0.097 | 0.578 | 0.324 | 0.493 |

| 0.384 | 0.501 | 0.522 | |

| 0.048 | 0.285 | 0.160 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

below | 104 | 314 | 119 | 537 |

| 20.530 | 0.235 | 12.604 | |

| 0.194 | 0.585 | 0.222 | 0.310 |

| 0.481 | 0.318 | 0.224 | |

| 0.060 | 0.181 | 0.069 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

Column Total | 216 | 986 | 531 | 1733 |

| 0.125 | 0.569 | 0.306 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

Frequencies are displayed in each cell. The frequencies or cell counts in each cell can be converted to percentages (N/Row Total). Within each category of income, the percentage for the three categories of happiness is displayed. Thus, of the 342 people who reported their family income as above average, 135 reported themselves as very happy (39.5%). By contrast, 119 (22.2%) of the 537 people who reported below average family income, reported they were very happy.

You can reduce information in each cell by running the code below

CrossTable(data$Income, data$Happy, prop.t=FALSE, prop.r=FALSE, prop.c=FALSE) #To hide proportions in the rows and columns

Cell Contents

|-------------------------|

| N |

| Chi-square contribution |

|-------------------------|

Total Observations in Table: 1733

| data$Happy

data$Income | not | pretty | very | Row Total |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

above | 29 | 178 | 135 | 342 |

| 4.356 | 1.413 | 8.709 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

average | 83 | 494 | 277 | 854 |

| 5.163 | 0.135 | 0.898 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

below | 104 | 314 | 119 | 537 |

| 20.530 | 0.235 | 12.604 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

Column Total | 216 | 986 | 531 | 1733 |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

Conditional percentages show the distribution of proportions in one variable, conditional on the other variable - hence, also called conditional distributions. For example, the conditional distribution of happiness for those who reported average income are 9.7%, 57.8%, and 32.4%. They can also be interpreted as conditional probabilities. Given that an individual reported average family income, the probability of not being happy, or pretty happy, or very happy is 9.7, 57.8, and 32.4, respectively.

Marginal proportions refer to the values in the margins of the contingency table. The marginal proportion of people who reported not happy, pretty happy, or very happy is 0.125(12.5%), 0.569(56.9%) and 0.306(30.6%), respectively.

To perform a Chi-squared test with the CrossTable() function, we can add some arguments to the previous code.

CrossTable(data$Income, data$Happy,

#fisher = TRUE, #To get fisher's exact test

chisq = TRUE, #To get pearson chi-square statistic

expected = TRUE, #To get the expected cell counts (which should be > 5 in each cell)

)

Cell Contents

|-------------------------|

| N |

| Expected N |

| Chi-square contribution |

| N / Row Total |

| N / Col Total |

| N / Table Total |

|-------------------------|

Total Observations in Table: 1733

| data$Happy

data$Income | not | pretty | very | Row Total |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

above | 29 | 178 | 135 | 342 |

| 42.627 | 194.583 | 104.791 | |

| 4.356 | 1.413 | 8.709 | |

| 0.085 | 0.520 | 0.395 | 0.197 |

| 0.134 | 0.181 | 0.254 | |

| 0.017 | 0.103 | 0.078 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

average | 83 | 494 | 277 | 854 |

| 106.442 | 485.888 | 261.670 | |

| 5.163 | 0.135 | 0.898 | |

| 0.097 | 0.578 | 0.324 | 0.493 |

| 0.384 | 0.501 | 0.522 | |

| 0.048 | 0.285 | 0.160 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

below | 104 | 314 | 119 | 537 |

| 66.931 | 305.529 | 164.540 | |

| 20.530 | 0.235 | 12.604 | |

| 0.194 | 0.585 | 0.222 | 0.310 |

| 0.481 | 0.318 | 0.224 | |

| 0.060 | 0.181 | 0.069 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

Column Total | 216 | 986 | 531 | 1733 |

| 0.125 | 0.569 | 0.306 | |

-------------|-----------|-----------|-----------|-----------|

Statistics for All Table Factors

Pearson's Chi-squared test

------------------------------------------------------------

Chi^2 = 54.04308 d.f. = 4 p = 5.154502e-11

Following is the Chi-squared statistic and corresponding p-value for the test of independence under the null hypothesis that, income and happiness are independent (no association). Since the p-value is very small (< .05), we can reject the null hypothesis. Thus, there is an association between family income and happiness.

In other words, the observed association between family income and happiness in the sample data reflects a true association in the population, and it is very unlikely to have occurred by chance if the null hypothesis was true. Find out the problem with this conclusion here

chisq.test() functionWe can also use a different function to perform the Chi-squared test. Here, we use the chisq.test() function in the stats package, which also contains many other functions.

chi.test <- chisq.test(data$Income, data$Happy)#Create and object called chi.test and assign the result of the chisq.test function() into this object

chi.test #Call the object to see its contents

Pearson's Chi-squared test

data: data$Income and data$Happy

X-squared = 54.043, df = 4, p-value = 5.155e-11chi.test$expected #To get expected cell counts. data$Happy

data$Income not pretty very

above 42.62666 194.5828 104.7905

average 106.44201 485.8881 261.6699

below 66.93133 305.5291 164.5395The residuals show the difference between the observed counts and what the model predicts (the expected counts/frequencies) in a particular cell computed under the null hypothesis. The standardized residual is similar to the z-score and indicates the number of standard deviations that an observed count falls from its expected count. If the value of the standardized residual lies outside of +/-1.96, then it is significant at p < .05; if it lies outside +/-2.58, then it is significant at p <. 01 and when outside +/-3.29, then it is significant at p < .001.

chi.test$stdres #Assuming there is a significant result, the standardized residuals can help us to understand the patterns of association data$Happy

data$Income not pretty very

above -2.4899518 -2.0210658 3.9551662

average -3.4099626 0.7870470 1.5977872

below 5.8295149 0.8885336 -5.1313795For example, if we take the first cell - (i.e., people who reported above average family income, and not happy). We can say that, the observed count is 2.49 standard deviations below (because of the negative sign, -2.49) the expected count for this particular cell. The substantive interpretation is that, for people with above average family income, many fewer were not happy than what the model predicted or, in other words, what the assumption of independence between income and happiness would predict.

We can interpret positive standardized residuals first, followed by negative standardized residuals.

For standardized residuals 5.83 and 3.96, the observed count is much higher than the expected count (more than 3 standard deviations higher). For people who reported below average family income, many more were not happy. For people who reported above average family income, many more were very happy.

For standardized residuals -3.41, -2.02 and -5.13, the observed count is much lower than the expected count. For people who reported average family income, much fewer were not happy. For people who reported below average family income, much fewer were very happy.

Overall, the association between income and happiness seems to be driven by average to above average family income, and much more so, by above average family income.

The Chi-squared test does not tell us where in the cell counts or frequencies the difference from independence lies, that is why the standardized residuals are useful for interpretation and understanding the patterns of association between the variables.

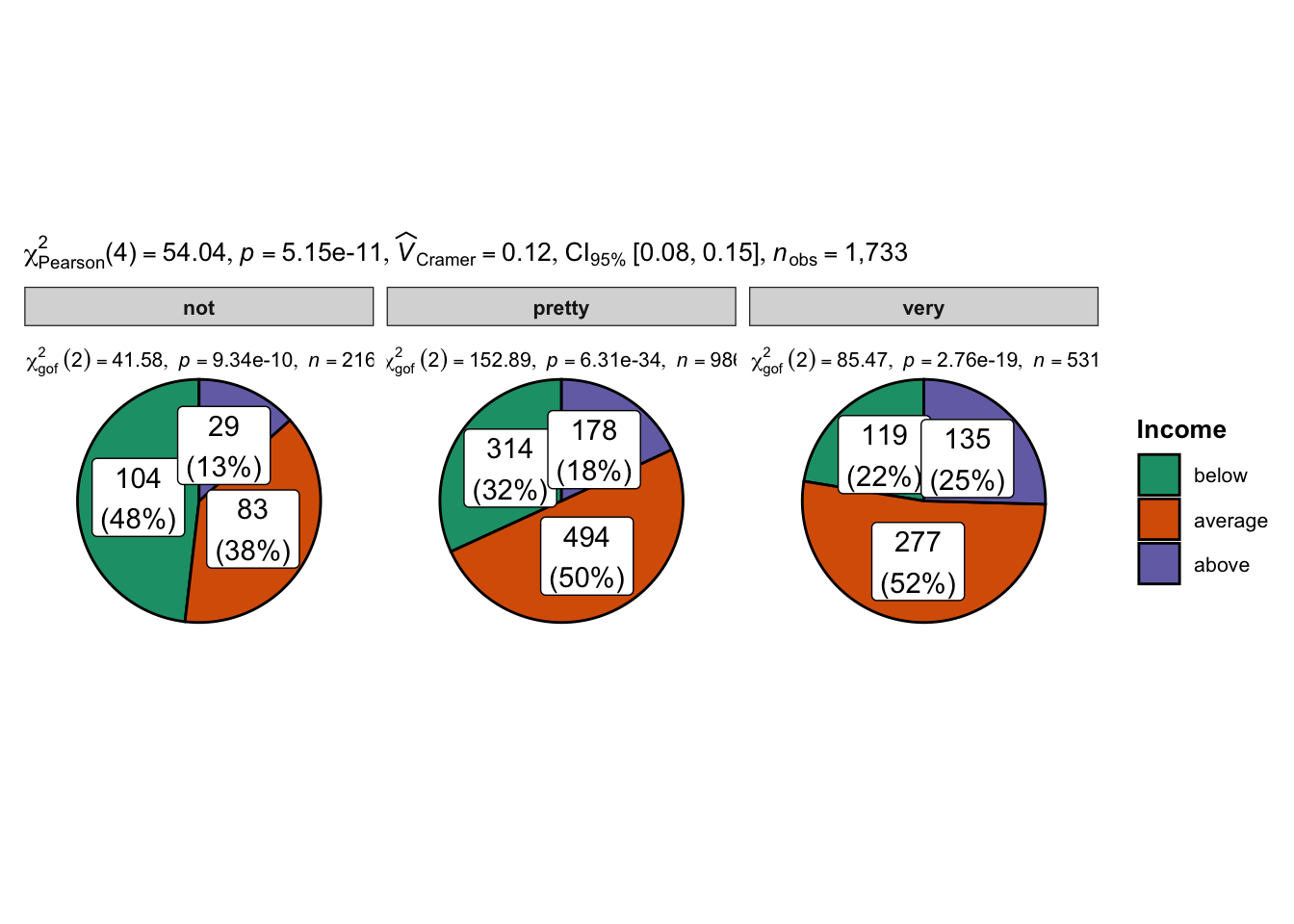

ggpiestats() and ggbarstats() functionsWe can also use the ggstatsplot package for this exercise. This package “creates graphics with details from statistical tests included in the plots themselves. It provides an easier syntax to generate information-rich plots for statistical analysis of continuous (violin plots, scatterplots, histograms, dot plots, dot-and-whisker plots) or categorical (pie and bar charts) data”. See here

library(ggstatsplot) #Load the package to access the functionsYou can cite this package as:

Patil, I. (2021). Visualizations with statistical details: The 'ggstatsplot' approach.

Journal of Open Source Software, 6(61), 3167, doi:10.21105/joss.03167By plotting a pie chart, we also get the results for the Chi-squared test

ggpiestats(data = data,

x = Income,

y = Happy,

label = "both")

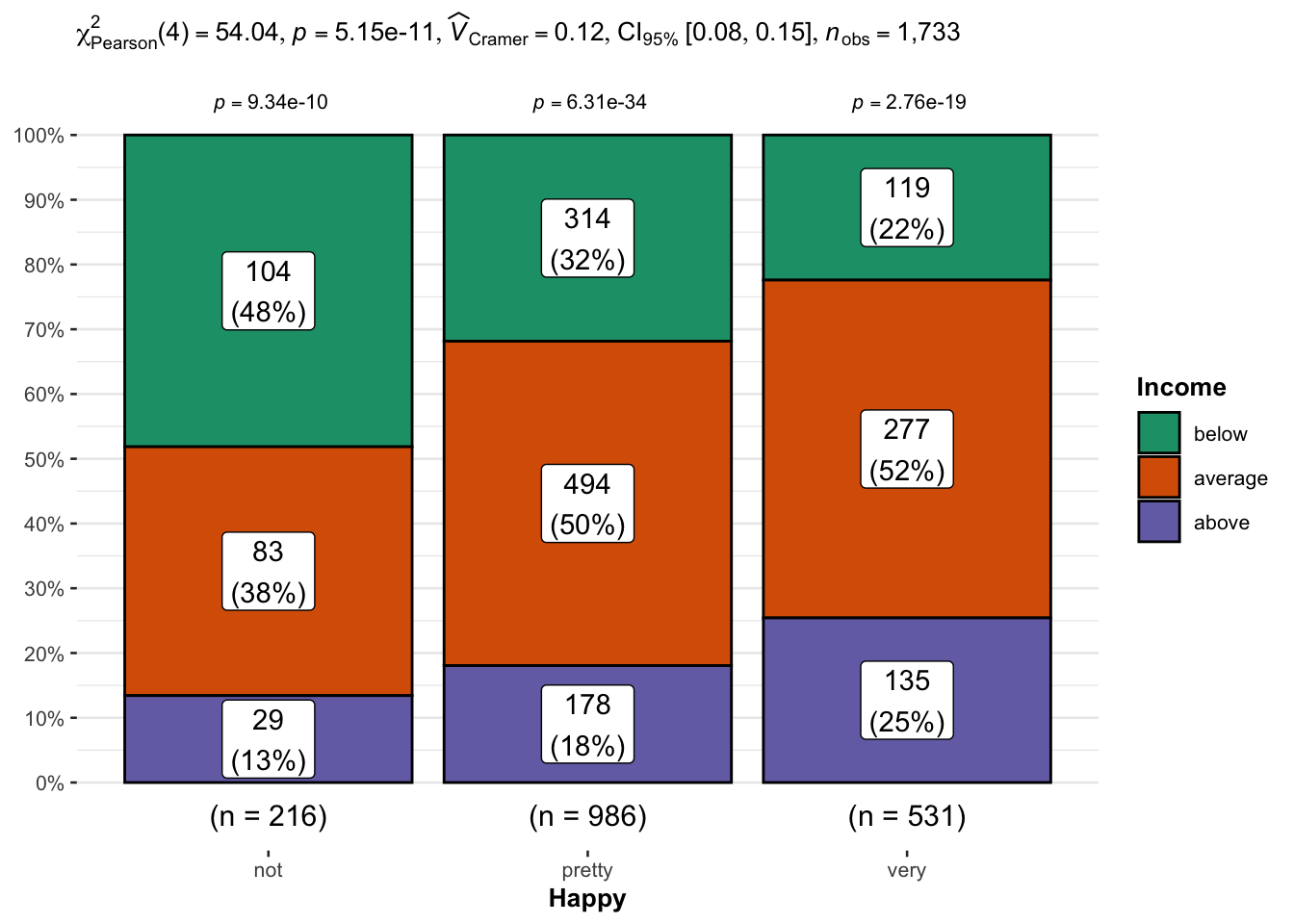

We can also perform and visualize the Chi-squared test of independence using the ggbarstats() function when we call the function to plot a stacked bar graph.

ggbarstats(data = data, #The first argument is the data

x = Income, #The variable to use as the rows in the contingency table

y = Happy, #The variable to use as the columns in the contingency table.

label = "both") #You can use "percentage" or "count"

As can be seen, the proportion of people who reported below average family income reduced with increasing happiness whereas the proportion of people who reported above average family income increases with increasing happiness. This support the previous conclusion that, the association between income and happiness seems to be driven by above average family income.

This function automatically outputs the Cramer’s V with its 95% Confidence Interval next to the p-value. The effect size of .12 is a relatively weak association. It also provides a corresponding Bayesian effect size, which is much more useful. There is also a Bayes factor, which tests both the null and alternative hypothesis at the same time. The designation of ‘01’ returns a Bayes Factor in favor of the null hypothesis whereas ‘10’ returns a Bayes Factor in favor of the alternative hypothesis. The Bayes factor shows that the null hypothesis does not do well compared to the alternative hypothesis. This is evidence in favor of the alternative hypothesis that, there is an association between family income and happiness.

Finally, this function shows the proportion test for family income (below average, average and above average) in each category of happiness (not happy, pretty happy, and very happy) under the null hypothesis that the sample proportions are not equal. They show whether the proportions inside each category of happiness differ. Since the p-values are all very small, we can conclude that the sample proportions of family income within each category of happiness differs. This type of Chi-squared test is referred to as the Chi-squared goodness-of-fit statistic, used to test hypothesis involving a single categorical variable from a single sample.